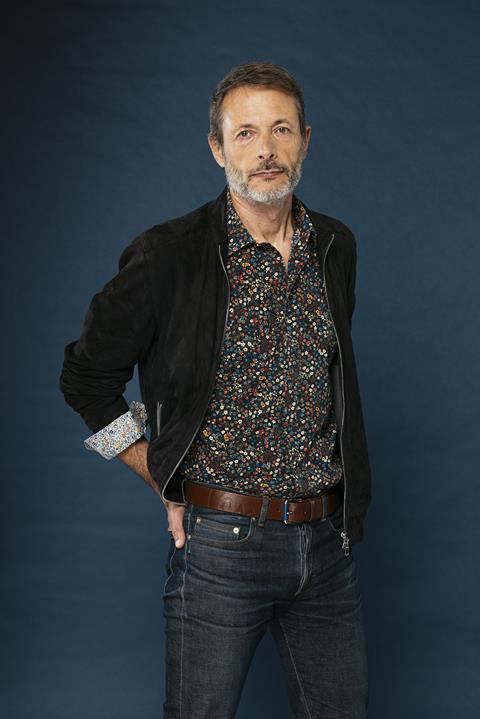

Oscar winner Jean-Xavier de Lestrade on turning the true story of hostages from the 2015 Paris terror attacks into a hit miniseries

It is exactly 10 years ago today since Paris was rocked by the 13 November terrorist attacks, which saw armed gunmen storming the Bataclan concert hall.

Coinciding with the anniversary, France’s resident king of the true crime drama Jean-Xavier de Lestrade is back with mini-series Those Who Lived (Des Vivants), which focuses on seven survivors held hostage during the attacks who went on to form a unique friendship as they rebuilt their lives after the trauma.

The eight-part series, which was launched to buyers by Federation International at Mipcom last month, has been stirring up emotions domestically following its 27 October release on streamer France.TV. A primetime linear debut on France 2 followed on 3 November, and de Lestrade is keen to address what the show is – and is not.

“It’s not a series about the Bataclan attacks,” he explains to Broadcast International. “It is a series about reconstruction and how to take one’s life back after living through the most extreme barbary imaginable. And the answer is through connection with other people.”

The series focuses on concert goers at the Eagles of Death Metal concert who were taken hostage in a narrow corridor during the attack, coming face to face with armed terrorists strapped with explosive belts for several hours before being evacuated by Paris police unit the BRI.

They ended up meeting after the attacks and nicknamed themselves ‘les potages’, a portmanteau combining the word ‘pote’ meaning friend and ‘otages’, which means hostages. Over the course of the past decade, they have maintained a close bond and helped each other to continue living despite the trauma they incurred.

Surviving trauma

The series is an intimate portrait of fictionalised versions of the seven hostages, played by actors Benjamin Lavernhe, Alix Poisson, Antoine Reinartz, Félix Moati, Anne Steffens, Thomas Goldberg, and Cédric Eeckhout.

“Their story is universal. It’s about how people survive trauma, whether a violent terrorist attack or something else. It’s about how they take their lives back and go on living, how their friends and family react, how they heal themselves,” says De Lestrade, who directed the series he co-wrote with Antoine Lacomblez.

It is produced by Matthieu Belghiti for What’s Up Films, Jérôme Corcos for NAC Films and Nicolas Mauvernay for Mizar Films. Federation International is handling international sales.

De Lestrade, who won an Oscar for his documentary Murder On a Sunday Morning, is no stranger to tackling sensitive topics. He was behind Netflix docuseries The Staircase about Michael Peterson, a crime novelist accused of killing his wife Kathleen, and last year’s hit six-part thriller series Samber, about a French serial rapist.

The latter show broke records when it became France.tv’s most-watched series last year, with the series going on to be sold to more than 50 countries including the BBC in the UK.

Now, he is taking on a story about the aftermath of the coordinated mass shootings and bombings that left 130 people dead and nearly 500 injured in the centre of the French capital a decade earlier but employing a different approach.

“There was no question in our minds - we did not want to show images of dead bodies or glorify the terrorists by zooming in on their faces,” de Lestrade explains. Producer Mauvernay adds: “We represented the violence, but differently.”

Instead, the audience experiences what transpired that night through select scenes at the Bataclan with flashbacks to the night of the massacre and of the hostages in the hallway.

There are also the words used by survivors in therapy sessions as they describe what they say, as well as interactions with each other and their loved ones.

Genesis of an idea

The project originated in 2021 when producer Corcos spotted the real-life David Fritz Goeppinger on television talking about how he was taken hostage and the group of friends he made after the experience.

“I wrote to him saying, ‘I have an idea but I don’t know if it’s a good idea.’”

He met with Goeppinger, and producer Mauvernay then met with the group collectively and individually over the course of more than a year. Many were hesitant about the prospect of fictionalising their experiences and they agreed that if even one of them did not want to participate, the series would not be made.

Eventually, they agreed and producers contacted de Lestrade and sent him around 20 pages Goeppinger had written about his group’s experience. De Lestrade, however, was hesitant.

Having lived in Paris for more than 30 years and between the 10th and 11th arrondissements where the tragedy took place, he was “horrified, shocked and submerged by emotion” following the attacks.

When Corcos and Mauvernay first contacted him, “I felt I was experiencing those emotions all over again and thought I wasn’t capable of reliving that.” After more reflection, however, he changed his tune.

“I said, au contraire - if I as an auteur cannot deal with this, how can audiences and society move forward? These emotions needed to be digested and transformed into something more positive and fiction was the only way to tell this story.”

His long-time production partner Belghiti came on board and between May and June of 2023, de Lestrade and his writing partner Antoine Lacomblez met with each of the ‘potages’ individually, as well as with their significant others and police officers from the BRI, the French police unit tasked with responding to the hostage situation in 2015.

Three months later, they met with them again both to add more testimonial to the scripts and to share which parts of their stories they would be fictionalizing, to be certain each one was in agreement. “We were taking material from their personal lives so we needed their approval – we didn’t want to add more pain and suffering to their own,” de Lestrade says.

It is a form of resistance to say that there is light at the end of the tunnel and this light comes from human connection

Jean-Xavier de Lestrade

De Lestrade and Lacomblez worked together to sequence the episodes, then Lacomblez wrote the first version of the dialogue alone before the two read the scenes aloud together.

“Eighty per cent of the series is his dialogue,” de Lestrade says, crediting his writer. While some room was left for small improvisations on set, the actors work with mostly scripted material even if their chemistry on screen gives the series a more documentary feel.

“More than any other fiction I’ve done, people keep telling me ‘I felt like I was watching real people,’” he adds. Producers and de Lestrade spent time with the potages, but did not share scripts with them. “They never even asked,” Belghiti said.

Some actors met with their real-life counterparts during filming and each of the ‘potages’ visited the set. Some even have cameos in various episodes in the series, alongside some of the real members of the BRI who were part of the evacuation a decade ago.

Sensitivities in production

The series was filmed at the real locations where the attacks occurred, including Paris’ Boulevard Voltaire, a narrow passage on the rue Amelot, in front of and inside the Bataclan, and in the courtroom at the Palais de Justice where the trial took place. “I felt we had a moral obligation to shoot at the actual sites,” de Lestrade says.

The question of whether or not to film inside the Bataclan was also a major decision.

While Lestrade and his team made the creative choice not to show the violence of the massacre, he explains: “It was essential for us and for the hostages and police officers to film in the place where [the attacks] happened. We needed to show that so audiences would understand what had transpired, much like the hostages and officers needed to return to process the trauma.”

While initially denied permission to film inside the Bataclan, the ‘potages’ wrote a letter directly to the venue in which they explained the importance of using the venue and why it was important to tell the true story of what transpired within its walls. They were subsequently granted access.

When the series was finished, producers gathered the group for a screening of all eight episodes in a Parisian cinema before showing it to anyone else.

“Their approval was most important to us,” Belghiti says, adding: “Every single person who worked on this series - from the actors to the crew - felt a great responsibility.”

But Belghiti acknowledges the show is not for everyone. “For some people, it may hit too close to home and we understand some audiences won’t be able to watch it, and they shouldn’t. There is no ‘right’ way to deal with such a trauma, but we asked ourselves and the people involved all of these questions from the beginning.”

De Lestrade also says the show has plenty of contemporary relevance in a politically divisive world.

“We cannot forget solidarity and the values of freedom and unity we found in France after the November 13 attacks. This was a group of people who didn’t know each other, who had little in common, but they formed an indestructible bond that was stronger than their differences.”

Mauvernay agrees. “It shows that when people talk and respect and take time to listen to each other even after experiencing the worst things possible, there is something beautiful that can come of it.”

De Lestrade adds: “It is a form of resistance to say that there is light at the end of the tunnel and this light comes from human connection. It’s simple.”

No comments yet