On the frontline with an unlikely revolutionary

Production company Hopscotch Films

Commissioner Kate Townsend

TX 9.50pm, BBC4, 23 July

Executive producers Alex Gibney; Nick Fraser; Kate Townsend; Ross Mckenzie

Producer/directors John Archer; Clara Glynn

Writer Carne Ross

Editor Berny McGurk

Music Paul Leonard-Morgan

Post houses Savalas; Serious

Distributor TVF

Three years after we started filming what became Accidental Anarchist, I took a day return from Glasgow to Euston to meet the UK representative of the self-governing institutions of Rojava, the predominantly Kurdish area of north-east Syria.

Alan Semo is a softly spoken, unassuming man, and also a London dentist. We met in a café opposite the station. Within the hour, we had sorted an invitation to film in Rojava. Two hours later, I was on the train home to Glasgow, confident that at last we had the climax of our film.

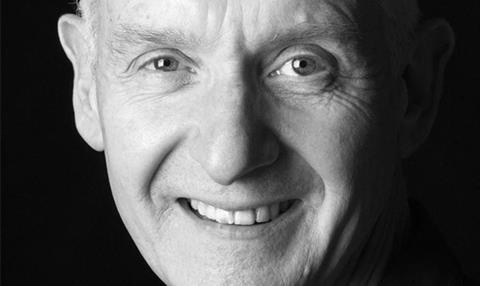

Accidental Anarchist started when I read Carne Ross’s book The Leaderless Revolution. Carne had been the UK lead on Iraq at the UN before the war, but resigned because of the lies his government told.

His evidence to parliament was instrumental in setting up the Chilcott Report. The book is a damning indictment of the system and a breath of fresh air. A feature documentary had to be made.

Raising money

A serious political film that involved a large number of overseas shoots was going to be a hard sell to a UK broadcaster.

We decided that the best way to get it made was to raise some development money, fund it partially ourselves, and do enough filming to convince potential investors.

A few months later, with development funding from Creative Scotland, we were in the UN Security Council with cameraman Neville Kidd shooting a bravura hand-held sequence with Carne in the empty chamber. Carne talked of his deep personal shame at what he had helped his government do.

The next morning, we were with Carne on the streets of New York, reliving his personal memories of 9/11. That weekend trip to New York provided the spine of the film, and the material to pitch it with.

We took part in the first of the BFI’s public pitches at Sheffield Doc/Fest, a gladiatorial combat in front of an audience of industry peers. Pitch tutor Christina Burnet’s preparatory workshop was crucial in honing the idea, and settling on a title.

We failed with the BFI, but we got a commitment from SBS in Australia, interest from Nick Fraser for Storyville and production funding from Creative Scotland.

When we later pitched in Toronto and Copenhagen, Nick and Mette Hoffman Meyer, head of documentaries and co-productions at Danish broadcaster DR, introduced us with passionate enthusiasm.

The film combines two stories: Carne’s personal journey from Foreign Office high-flyer, through his disillusionment with the government’s duplicity over the Iraq war, WMD and David Kelly’s suicide; and a second, broader story about anarchist alternatives to government and how they work.

Carne’s personal story takes us there – but the balance was a constant debate in our weekly Friday conference calls with him in New York.

My fellow PD, Clara Glynn, is also my wife. Because of the time difference, our calls with Carne usually happened in the evenings. Pretty soon, our 10-year-old son banned us from talking about him.

Meanwhile, editor Berny McGurk knocked the film into shape and found a way of using Carne’s passion to take the audience to the unfamiliar and complex ideas we wanted to explore.

One of the breakthrough moments was when we were struggling to find an image for the organised chaos of anarchism. We sourced a starling murmuration from British bird enthusiast Dylan Winter and ran it against Carne’s explanation of anarchism – it didn’t just make sense, it sang.

By this time, we had a new BBC exec, Kate Townsend, who viewed the cut and loved it.

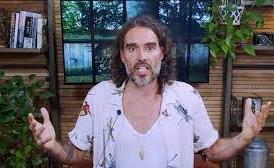

We’d filmed in Oxford, London, New York and Spain, but when Carne heard about the extraordinary quiet revolution happening in Rojava in Syria, we knew we had to include it in the film.

Here was today’s equivalent of the heady months in 1936 when Barcelona was run on anarchist principles. Carne was determined to go there.

John Archer - My tricks of the trade

- Value directors and help them achieve their vision. Good directors do their best work when they feel they have creative ownership of the film, so avoid micro-management.

- Make sure your own kit is fit for purpose, so more of the budget is seen on screen.

- Work and develop projects in areas where you have a strong track record.

- Watch the pennies so you can be extravagant on stuff that really makes a difference.

At this point, the Sundance Documentary Institute’s Stories of Change programme stepped in with a grant – just enough, and just in time to make the Syria filming possible.

As the edit was finishing and we were sorting the captions, I got in touch with Alan Semo again. I needed to check the name of one of the YPJ (Women’s Protection Units) fighters we’d interviewed, a young woman who was passionate and articulate about the battle against Isis.

He told me that Vijan had been killed last year in the battle for Al-Shaddadi. The film is dedicated to her.

ENTERING THE DANGER ZONE

Clara Glynn, Producer/director

We needed to be able to use minimal crew when filming in Syria and were looking for someone who knew the area. We found Javier Manzano via Facebook (it turns out that it’s not just for posting pictures of cats and holidays).

Javier is a Mexican-born American cameraman based in Turkey who had filmed in Rojava before.

A female journalist friend of Carne’s recommended a security adviser, whom she believed had saved her life on numerous occasions. Darren White was the rock this expedition needed.

Javier, Carne and Darren rendezvoused in Iraq, then drove 300km to the Syrian border. We’d been in touch with the Iraqi border guard who ran the river crossing to check they’d be allowed over (again via Facebook).

In the event, their biblical-looking crossing of the River Tigris went smoothly and they were met by their guides from the YPJ [Women’s Protection Units] on the other side.

Setting up a shoot in war-torn Syria as a small, independent company is quite a challenge. We’ve never had to buy body armour for our presenter before.

Isis has a horrible habit of kidnapping foreign journalists and our crew were filming eight kilometres from the frontline.

The security regime initiated by Darren sent us an automated message direct via text from his tracking device every 30 minutes to let us know that everything was fine.

If we failed to get the message, we were to contact his colleague, who would set in motion elaborate protocols that would lead eventually to a rescue or evacuation mission.

CONTINGENCY PLANS

There were also complex contingency plans in case of kidnapping that we’ve been asked not to be specific about. Carne would have been quite a catch.

The insurance cost for all of this was considerable. I’ve never been quite so relieved to get a crew home. But for Carne, it was a lifechanging experience.

His comment that if he didn’t have young children, he’d have wanted to stay in Syria made an epic end to the documentary. Because if they can create participatory democracy in Syria, surely we can change things for the better here?

No comments yet