Sponsored content

Sponsored content

Abbas Media Law provides tips to help producers understand what law apply in the Covid-era

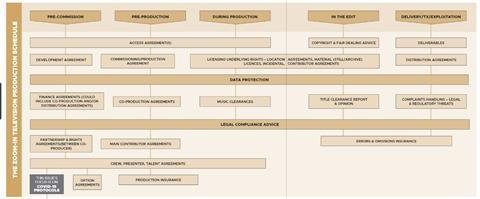

In every issue of zoom-in we examine the commercial, legal and regulatory hoops programme-makers have to jump through to get their programmes safely to air. Our production legal schedule above sets out the five key stages of production which producers need to consider and the advice and expertise they are likely to need at each stage. In each issue, we focus on one or two particular aspects of production legal requirements.

COVID-19: THE FACTS

With Covid-19 restrictions being re-imposed all over Europe, the winter looks full of uncertainty. So how can producers best manage Covid-19 legal and commercial risks over the next few months? Here are a few tips.

Is filming legal?

The first question is where you are filming, to determine which laws apply. Laws are likely to relate to restrictions on gatherings, the wearing of masks, who has to quarantine and for how long. The laws of multiple countries may apply if you are filming in different locations, or crew or contributors are travelling from one country to another. And, of course, the rules are different depending on where you are.

For example, whilst exceptions to restrictions on freedoms for ‘work purposes’ apply in most jurisdictions of the UK, the exceptions don’t all operate in the same way. Take restrictions on gatherings in private dwellings.

Whilst filming with a contributor showing you their antique clock collection in their home in England may be permissible because it is reasonably necessary for ‘work purposes’, and thus falls within an exception, the same filming may be illegal in Northern Ireland where the ‘work exception’ to restrictions on gatherings in private dwellings is drawn more narrowly.

And now, even within England, consideration needs to be given not only to the rules where filming is taking place, but to where a crew member or contributor resides, as rules and restrictions that an individual must comply with, depend not on where they are, but where they live.

A contributor from a city under Tier 3 restrictions must abide by those restrictions whether they are in Liverpool or rural Cornwall. The lesson to take from this – do your homework and try to anticipate how law might change which would affect future plans!

Is your production legal? Need to know what laws apply to your show? We advise on all relevant rules and ensure you stay on the right side of the law. We work with broadcaster and production companies of all sizes and have helped get some of TV’s biggest and most popular shows back on our screens in 2020. Contact ABBAS Media law at: info@abbasmedialaw.com

Health and Safety first

Never has health and safety been so centre stage in TV production. Consideration of all matters COVID-19, thorough risk assessments and implementing protocols and measures to minimise risk is now an essential pre-requisite of any commission and production.

Broadcasters, financiers and other commissioners are likely to insist upon it and, indeed, production may only be legal if a proper risk assessment has been undertaken and requisite health and safety measures put in place. Engaging and investing in experienced industry H&S professionals is a must.

Various helpful guidelines have been published to help guide and assist the UK production sector get back on its feet. Most are available on the PACT website: https://www.pact.co.uk/covid-19/production-guidance.html

Business affairs and underlying agreements

Making television is an expensive business with producers committing themselves to huge financial outlay from the start, albeit largely underwritten by commissioners, distributors and other financiers.

There are the outgoing financial commitments producers have to make to crew and others who work on the production, then there’s the money producers receive (or are promised) from commissioners, financiers and distributors in return for which they are contractually obliged to produce and deliver content. What, if anything, can producers do to protect themselves commercially and financially from a COVID-19 shutdown?

With underlying agreements, like those which oblige production companies to pay crew and others working on production, the key to managing financial risk is focussing on what the agreements say about force majeure, suspension, and termination.

Underlying agreements should include a right for producers to suspend an engagement for reasons of force majeure (extraordinary events beyond the parties control), so that no further fees are payable while a production is stood down, and allow for the engagement to continue after the suspension ends.

As to how long a suspension can continue, contractual provisions should be fair and reasonable, considering the specific circumstances. If an individual is contractually barred from accepting other engagements during a period of suspension and therefore cannot earn money, it would not be reasonable for suspension to continue for an extended period.

PACT has suggested a maximum of 21 days suspension for crew where they are unable to accept other work. However, if an individual is allowed to accept other work during suspension (provided they undertake to promptly re-take up their suspended engagement when required), it may be considered reasonable to keep the suspension in place for longer.

The right to suspend engagements in contracts should work together with the termination clause, which should state that producers can terminate an engagement if a force majeure event continues beyond a stated time period (whether there has been a suspension or not), so that if production is cancelled or decommissioned, the producer can cut off payment of fees from the date of termination, or the start of the prior suspension if there has been one.

The other main commercial risk for producers concerns the contractual relationship with broadcasters and other funders who either release, or promise to release, funds subject to contractual obligations being fulfilled by producers i.e. delivering content.

Most of the main UK broadcasters looked to revise their force majeure wording, or introduce new COVID-19-specific wording, after the lockdown eased to mitigate their financial risks, and to place risks primarily onto producers and in May 2020, PACT posted a note warning their members of the BBC’s, Channel 5’s, and ITV’s changes.

The BBC changes stated that if the production schedule for a programme is disrupted due to COVID-19, a revised commissioning specification should be completed by the producer within 6 weeks, and if revisions cannot be agreed, the BBC is entitled to terminate the agreement – the consequences of termination under the BBC General Terms is that cashflow is cut off at the point of termination.

Channel 5’s new wording granted the broadcaster a right to suspend and terminate if continued production might harm Channel 5 or Viacom’s reputation or be against either party’s internal guidance.

PACT and Channel 5 subsequently agreed that any such suspension must continue for more than 4 weeks before termination. PACT and Channel 5 have also agreed that both the producer and Channel 5 can suspend a production agreement if to continue production would be against government COVID-19 guidelines or instructions, and that if suspension continues for more than 4 weeks then either party may terminate, and that Channel 5-approved ‘pause and start up production costs’ resulting a Covid-19 suspension (and which are not covered by insurance) can be recouped from any underspend and in first position from net receipts.

The ITV changes stated that in the event of any COVID-19 delay to production, ITV would not pay towards postponement or associated costs on the basis that they only pay a licence fee on delivery and acceptance.

Channel 4 didn’t change their wording, probably because the force majeure clause in their general terms is sufficient to cover them (and I would expect the SVOD content commissioners to not be overly worried about changing their contracts either, on the same basis).

In order to try to manage the risk to producers of not being paid by commissioners/financiers in the event of a second lockdown, PACT lobbied for an insurance scheme to underwrite potential producer losses and on 28 July the Government announced the introduction of a UK-wide £500 million Film and TV Production Restart Scheme.

The Scheme makes direct compensation available to producers that incur costs caused by coronavirus abandonment or delays to eligible pre-existing and new productions.It was formally launched on Friday 16 October.

To be eligible a production must, amongst other things, have at least half the production budget spent in the UK. The Scheme provides compensation for costs up to a value of 20% of the production budget, with abandonment covered up to 70%. Where initially the deadlines for registration and start of PP were 31 December, this has been extended to 28 Feb 21.

Here is a link to the Government guidance on the scheme: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/film-tv-production-restart-scheme

And here is a link to the Marsh Commercial website where producers can apply to the scheme: https://www.marshcommercial.co.uk/campaigns/film-and-tv-restart-scheme/

Equality and discrimination in times of Coronavirus

Karon Monagahan QC, Matrix Chambers

Many businesses are concerned about exposing workers to Covid–19, and their obligations in relation to those at particular risk.

Some disabled people and older people are at greater risk of serious harm from Covid-19 and, depending on the circumstances, the law allows a business to refuse employment to a person because of disability or age. However, for this to be lawful, there must be a good reason for the refusal, and general assumptions about people are unlikely to be adequate.

‘Disability’ in law covers a range of impairments, many of which put a disabled person at no greater risk of developing serious symptoms from Covid-19 than anyone else; a recurrent depressive illness, or epilepsy, for example. This means that a blanket refusal to employ all disabled people, whatever the nature of their disability, would be unlawful.

Where the nature of a particular disability does put a person at greater risk of serious harm from Covid-19, it may be lawful not to hire them because of the risk posed to them and/or the risk of disruption to the business caused by absences, protective measures and so on.

Whether this is so will depend upon the nature of the disability, the extent of any increased risk, the risk of exposure to Covid-19 in the particular workplace, and whether the risk can be mitigated by introducing safety measures. The law imposes a duty on employers and contractors to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ for disabled people.

This duty may require a business to adopt specific protective measures or to make other adjustments to take account of the greater risk; for example, moving a disabled person’s place of work, compulsory medical mask wearing by the disabled person or across the whole workforce. The duty does not require a business to adopt all possible measures, only reasonable ones, but the duty is a serious one.

As for age, although a reasonable adjustments duty does not apply to age, great care must be taken to ensure that blanket stereotypes are not applied. Declining to hire people falling within a particular age group (eg. over 50s) may be lawful in certain circumstances. It is now clear that older people are at greater risk of serious adverse effects from Covid-19, including death.

Nevertheless, again the question arises as to the extent of any risk posed by the particular workplace and whether measures could be introduced to mitigate that risk.

A business is entitled to take account of the costs and disruption if special measures are to be adopted and/or from prolonged periods of absence due to Covid-19. For this reason the law recognizes that a balance must be struck between the interests of a disabled or older person and the needs of the business.

A business must ensure, however, that they have good reason for not employing a disabled or older person; that the risk has been properly assessed; that generalised assumptions have not been made about all disabled or older people; and that mitigating measures have first been considered, before refusing to hire someone because of disability or age. If they do not, they risk being found to have acted unlawfully.

Karon Monaghan QC is an expert in equality and human rights law with experience advising the television and other creative industries www.matrix.co.uk.member/karon-monaghan

![Eleven [Jamie Campbell, Joel Wilson]](https://d11p0alxbet5ud.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/8/1/7/1472817_elevenjamiecampbelljoelwilson_770737.jpg)