Combining a murder investigation with a family history series made for a unique format – and may right some historical wrongs, says executive producer Mike Benson

Production company Chalkboard TV

Commissioner Lindsay Bradbury

Length 10 x 60 minutes

TX Stripped at 9.15am from 26 February, BBC1

Executive producers Mike Benson; Warwick Banks

Producers Lorna Hartnett; Hannah Eastwood (pilot)

Series producer and director Simon Cooper

Post house Radiant

What if you could create a show that combined the heart of Who Do You Think You Are? with the investigative rigour of Making A Murderer? That was the thinking behind the development of Murder, Mystery And My Family.

We’d just watched a BBC4 documentary that outlined the leaps and bounds in forensic science over the past 40 years, from DNA and bloodstain pattern analysis all the way through to ballistics.

This led us to think about how there must be hundreds of capital cases from before 1965 – the year capital punishment was abolished – where the evidence would have been purely circumstantial.

What if you could re-examine these cases through a modern forensic prism? Would they still stand up? And what if you were following the investigation through the eyes of a relative of the convicted and executed?

Out of these questions, our concept for Murder, Mystery And My Family was born: relatives of those executed for murder teaming up with barristers to reinvestigate the case, re-examine the evidence – and, potentially, clear the family name.

The show was commissioned in the most unexpected of places – BBC Daytime – by Lindsay Bradbury and Dan McGolpin. They had asked us to pitch things we wouldn’t normally bring to daytime, so we quickly ditched Bargain Hoarders In The Sun For Less and pitched this.

Budget was our first challenge: making essentially 10 bespoke documentaries on a daytime tariff is quite a stretch. What helped us was securing a distribution advance from Sky Vision — crime is always a popular area internationally and the distributor saw the potential in both the finished tape and the format.

Filming jigsaw

For the on-screen talent, it was vital that we didn’t use ‘TV barristers’. We needed people with both credibility and a passion for this area of the law, so we brought on board QCs Jeremy Dein and Sasha Wass.

One of the major challenges was creating a production schedule out of the jigsaw of these working barristers’ availability. In the end, we filmed around their holidays and weekends.

Jeremy looks at the cases from a defence perspective and Sasha from the prosecution’s viewpoint. The cases are then presented to a retired High Court judge, who decides if there is enough evidence for them to be put to the Criminal Cases Review Commission, an independent public body set up to investigate possible mis carriages of justice.

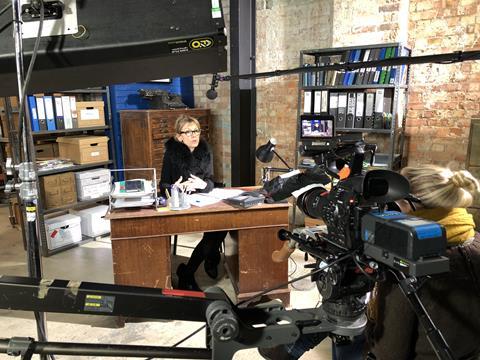

We converted the office into ‘CSI Chalkboard’ and brought in specialist legal researchers to help us source cases and the relatives of those convicted. It was quite an eye-opener to watch series producer Simon Cooper and his production team delve into cases that had long mouldered in the archives.

Mike Benson - My tricks of the trade

-

Make sure there isn’t a disconnect between what was pitched and what is produced. Often the very thing that got you the commission gets diluted in the rough and tumble of production, but that core top-line pitch is sacrosanct and must be fought for.

- If you don’t remain excited about what you’re making, no one will be excited watching it.

- The right editor is as important as the right senior producer. We are trying to involve our editors earlier in the production process to avoid them turning into psychotic grinches when they realise the rushes don’t have what they need.

- Getting past the point of eternal doom – that tearful moment, usually halfway through the edit, where the finish line is but a distant dream – is key. In every edit, it’s usually darkest before the dawn (usually because you’re in the edit at 4am eating Curly Wurlys).

Across the series, there were some startling revelations and in a number of cases, convictions were found to be unsafe.

Obviously, looming over every case, and of which we were acutely aware, were the shadows of the victims of the crimes and their families. For us, objectivity and balance was key.

While the relatives of the accused understand ably wanted to clear the family name, the barristers emphasised throughout that the investigation might actually do the opposite and reaffirm the conviction.

It was fascinating to explore the impact of the convictions on the families of the accused and executed. In some cases, it was never talked about.

In fact, a number of our contributors had no idea that their relative had been executed. In other cases, the family had disintegrated completely under the shame and strain of the conviction.

We had several reunions between family members, which was a powerful dimension that we hadn’t anticipated.

In one case, the family had emigrated to Australia. Our contributor returned to the UK to face the past and investigate the conviction with Jeremy and Sasha.

Murder, Mystery And My Family has been one of the most challenging series we have ever made, in every sense: legally, ethically and financially. But we believe the result is genuinely intriguing, balancing science and legal argument with real human stories.

FINDING POTENTIAL MISCARRIAGES OF JUSTICE

Lorna Hartnett - producer

While hundreds of serious criminal cases ended in execution before the abolition of capital punishment in 1965, not every hanging case is a potential miscarriage of justice.

When it came to finding the stories and casting the contributors for each episode, the first hurdle was to narrow down the pool of potential murder cases to those where legitimate questions had been raised about the original verdict, either at the time of the trial, appeal or execution, or in the years that followed.

EXTENSIVE RESEARCH

This was done through extensive research, poring over contemporary newspaper reports, modern true-crime books and the original trial material using the amazing historical resource that is the National Archives at Kew.

We were hunting for key evidence that had been overlooked at the time, witnesses who were never called and new information that had only surfaced once it was too late for the condemned man or woman to be reprieved.

Once we had identified the stories with the most potential for new material to be unearthed by a modern investigation, we next had to identify and contact the descendants of those who had been found guilty of murder.

For some, this was a stain that had long blackened the family name. Others had been trying for generations to get the original verdict overturned.

Many had never heard of this dark chapter in their family’s past, so all communication had to be handled with extreme sensitivity.

Some relatives were unwilling to revisit the pain, while others were eager to learn not only more about the case itself, but also what life was like for their ancestor in 1900s Newcastle, 1930s Oxford or rural Ireland at the turn of the 20th century.

Some family members were convinced that the barristers would find new evidence to put before the judge because, to the family, it had always been obvious that their ancestor’s guilty verdict had been a mistake.

Others had spent most of their lives believing their family member to be a murderer, only to discover that they may have been executed in error.

No comments yet