We had planned to make a film marking the 60th anniversary of the Notting Hill race riots, but after the Grenfell Tower fire, it was clear we had a bigger story to tell, says Alistair Pegg

Production company Blast! Films

Commissioner Simon Young (BBC)

Length 1 x 60 minutes

TX 13 June, 9pm, BBC2

Executive producers Alistair Pegg; Edmund Coulthard

Editors Tom Dixon-Spain; Niels Bellinger

Producer Amy Morgan

Producer/director James Ross

We started this project before the Grenfell Tower fire. The idea was to mark the 60th anniversary of the 1958 Notting Hill race riots by teasing out how its ramifications had played out all the way to now.

That sense of how history shapes the present remained part of our film’s DNA, even as it grew and changed almost beyond recognition in the wake of the disaster.

When the fire happened, we all knew an event of such enormity would change any ideas we had about how to tell the history of this part of London. It became clear that in the longer history was a story about inequality, and about the tower itself, that had never been told.

And so, in conversations with BBC history commissioning editor Simon Young, our Notting Hill race riots film expanded and changed. It turned into the story of an area that slowly but surely, over 150 years, had become the most unequal in the whole country.

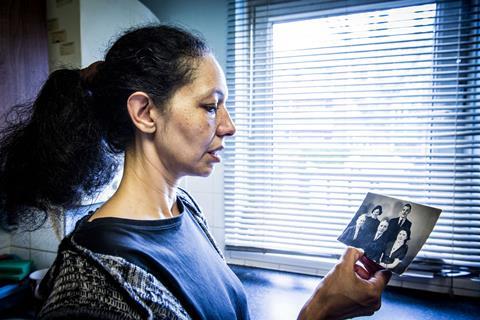

Crucially, we wanted this history to be told by the residents of the community around the tower. As we met more and more local people, we realised that their own family histories showed how inequality began and grew here.

We met Alan, who told us about a wall built in the 1860s, intended to physically separate new homes for the middle classes from what was then London’s worst slum: the Piggeries. The wall still runs along the bottom of his garden.

Laura told us how her great-grandfather came to Kensington in the 1930s in search of work, as part of the Jarrow March. Her grandmother became a serving maid in one of Kensington’s wealthiest households.

There was Vee, who came to London from Trinidad in the late 1950s expecting a warm welcome from ‘the mother country’ – but was forced to rent a flat from the notorious landlord Peter Rachman.

And then, after months of work, James Ross, our director, and his team tracked down locals who had been among the first to move in to Grenfell Tower when it opened in 1974.

Now the film really fell into place. For these residents, the tower had been a symbol of hope – and concrete proof that old injustices had been left behind. They were right to feel optimistic.

When Grenfell opened, Britain was more equal than it’s ever been – before or since. It had been wildly unequal before, and was to become so again: today, we have the same level of income inequality as we did in the 1850s. But for a moment, when Grenfell was new, Britain had achieved a kind of social justice. That moment became the hinge point of the film.

Back to the start

It’s a complex story that unfolds over 150 years. One of our biggest challenges was in the edit, working out where you start a story like this. In the present, with the fire or in the ’70s, when the tower opened? Or back in the 19th century, when today’s Kensington first took shape?

Of course, graphics helped, showing the ebb and flow of rich and poor across the borough over time. James filmed beautiful travelling shots of Kensington’s streets – including one road where homes sell for £8m each, while just around the corner is an estate with one of the highest levels of child poverty in the country.

Our archive team worked miracles, finding obscure and wonderful material – at one point in the edit, we were knee-deep in 600 different archive clips. But ultimately, the answer lay in letting our residents’ voices carry us through the history – theirs and their community’s.

Time and again, locals told us that few had been interested in their history before. But we were – and we wanted their stories to carry the film.

Alistair Pegg - My tricks of the trade

-

Keep re-reading your original proposal throughout the shoot. The film will evolve as you make it, but it’s easy to lose sight of the big picture.

- Keep the commissioning editor aware of the challenges and involved in all the big decisions.

- Write the Radio Times billing during the edit – to help boil down the film you’re trying to cut.

- Find some secure bike parking near the edit so your saddle doesn’t keep getting stolen.

We were surprised by the depth and range of their knowledge of social history, back to the 1850s and even earlier. We were struck too by how much local residents understood the tragedy of Grenfell in terms of the long history of this place.

And so the film became that rare thing, a history story that matters in the present, told by ordinary people.

CONNECTING THE AREA’S PAST AND PRESENT

James Ross - Producer/director

When production began, it quickly became clear that making a history film so soon after the Grenfell tragedy was going to be difficult. It was only three months after the fire and North Kensington remained a deeply traumatised community.

Understandably, the residents’ energies were totally focused on grief and justice. People were too busy dealing with what was in front of them to take a step back and think about Victorian slums, race riots and the origins of social housing.

SUSPICION OF THE MEDIA

Added to this was a deep suspicion of the media. By then, almost all the cameras and reporters that had been omnipresent in the days after the fire had moved on. But the community remained, and for them nothing had changed: those who’d been forced to move out of Grenfell and the Lancaster West Estate still hadn’t been rehoused.

Justice seemed far off. By November, much of the initial wave of anger had given way to exhaustion and fatigue. Throughout this period, we had been steadily getting to know members of this densely linked community. We didn’t approach any survivors of the fire, aware that in their grief, another documentary crew probably wasn’t what they needed.

Instead, we got to know many of the old-school residents who’d lived in North Kensington all their lives.

Though there isn’t a person there who wasn’t affected by the fire, by the new year, these residents seemed ready to connect the past and present and articulate that, in some ways, Grenfell was nothing new. It was the latest chapter in a long history of injustice and adversity.

As musician and community activist Niles Hailstones says in the film: “We are a community that has been dismembered and it’s about putting the pieces back together.” For many, their shared history felt like a natural place to start.

Our patience resulted in some of the most powerful and natural interviews I’ve ever done. As one contributor would often say in the early months of production: “There’s no point trying to tell someone something until they are ready to listen.”

Likewise, perhaps there’s no point trying to do an interview until people are ready to talk.

![Eleven [Jamie Campbell, Joel Wilson]](https://d11p0alxbet5ud.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/8/1/7/1472817_elevenjamiecampbelljoelwilson_770737.jpg)

No comments yet