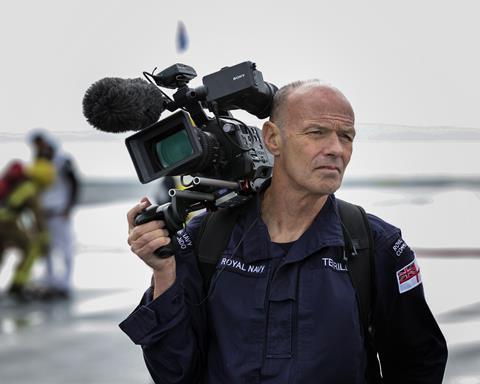

To understand the lives of the crew on board HMS Queen Elizabeth, I had to immerse myself in their culture, muck in with their work and learn how to speak like a sailor, says Chris Terrill

Production companies Uppercut Films; STV Productions

Commissioners Tom Coveney (BBC); David Royle (Smithsonian Channel)

Executive producers Chris Hall; Alan Clements

TX Sunday, 27 October (BBC2)

Length 3 x 60 minutes

Narrator Caroline Catz

Writer/director/cameraman Chris Terrill

Post house Timeline Television

Don’t tell the BBC, but if it hadn’t given me the money to make Britain’s Biggest Warship: Goes To Sea, I would have mortgaged my house and funded it myself – come to think of it, don’t mention that to my wife, either.

It was a life-cancelling experience but a life-changing one too, as I joined super-carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth on a gruelling four-month deployment to the Eastern Seaboard of the US.

In that time, we confronted snooping Russian warships, landed the first F-35 stealth fighter, sailed into full-blown hurricanes, had six of our sailors arrested in Florida, suffered floods and fi res, and anchored next to the Statue of Liberty on a spectacular visit to New York.

It was endlessly exciting, occasionally dangerous, regularly uproarious and frequently emotional but always inspiring. The process of filming, however, was not without its challenges: physical, creative and technical.

As an anthropologist-turned-filmmaker, I choose to work entirely alone so I can embed myself in communities for extended periods of time. This allows me to suspend my world view and begin to see things through the eyes of others – in this case, a ship’s company of some 1,200 sailors, marines and aviators.

When making this series’ predecessor, Britain’s Biggest Warship, in 2018, I developed a deep fascination with the ship’s state-of-the-art engineering – but only as a backdrop to the human stories that unfolded within.

Jerry Kyd, the captain, summed it up perfectly: “This ship is just a metal box full of wires, pipes and painted grey. Without people to breathe life into her, she’s useless.”

I took that as my guide from day one, but winning the trust of this tight-knit and dedicated community didn’t happen overnight.

To make both series – filming was more or less contiguous – I lived on the warship for a total of two years, including six months spent entirely at sea, not as an outside observer but as an active member of the ship’s company.

Anthropologists call this approach ‘participant observation’ and it’s one I’ve used many times in the field, especially when working among the Nilotic tribes of Southern Sudan. I determined to try it on the Queen Elizabeth – there is nothing more tribal than the crew of a warship.

I needed to comprehend their cultural mores, norms, taboos, unwritten laws and expectations of behaviour, including traditions and conventions. Plus, of course, I had to learn their language. Naval language – ‘Jack speak’ – is rich, vibrant and expressive, although much is unprintable.

To all intents and purposes, I became one of the crew, even though I carried a camera most of the time.

Chris Terrill - My tricks of the trade

-

Go with the flow. Don’t be too diverted by your original proposal or try to bend your filming around what you expected the story to be. What happens in real life is always going to be better than what you made up in your treatment.

- Observational filming takes over your waking and sleeping hours, so if you find time to relax, take something to divert and massage the mind. My travelling companion is Frasier – I know all the scripts virtually by heart.

- Bin bags and gaffer tape make the best raincoats for cameras.

- If you’re starting off as a self-shooter, concentrate your efforts on sound recording. You can get around dodgy or absent pictures but without good sound, you haven’t got a film.

- If you’re filming with the Navy, don’t leave your stills camera lying around. They’ll nab it and take some (very) personal portraits.

I wore a working uniform just like every one else and mucked in on cleaning duties. I had my own role for emergency stations, took part in the rigorous fitness regimes and even represented the ship in sporting events against other ships.

The main difference was I carried no rank or authority, but that worked in my favour. Like a naval chaplain, I assumed the rank of whoever I was talking to, so one minute I was a commodore, the next a midshipman and the next a marine engineer or stoker.

I had free run of the ship from the bilges to the bridge, so could search out my characters and respond to events as they unfolded.

Physical demands

Social interaction and cultural assimilation were one part of the production but the physical and technical demands of filming were quite another. The ship is truly gigantic – 280 metres in length with 3,200 compartments and five kilometres of passageways over 17 decks.

I often had to move fast in confined spaces, especially if the general alarm signalled a fi re or flood, so I limited my equipment to just what I could carry: my FS7 camera and a small rucksack containing batteries, second lens, radio mics and camera cards.

I never used booms or tripods – apart from a short monopod to give me extra grip when shooting from helicopters.

Participant observation served me well. It got me close to people who will be friends for life and gave me intimate insights into a ship that’s already an iconic symbol of nation.

It allowed me to witness extraordinary feats of flying by Naval test pilots and incredible feats of seamanship by the best-trained sailors in the world. All that, and I didn’t have to mortgage the house.

NAVIGATING CHOPPY WATERS

Alan Clements - executive producer

When I left STV Productions in May, I was delighted to continue my executive producer duties on Britain’s Biggest Warship. Having seen the first series through some choppy budgeting waters to the safe harbour of critical acclaim and excellent viewing figures, I thought a second series would be plain sailing.

However, potential threats were on the horizon. We needed to carefully navigate between the commissioning timetables of the two broadcasters – the BBC in the UK and Smithsonian Channel in the US – the legal requirements of all parties, including the distributor, Red Arrow Studios International, and the Royal Navy itself.

All of that was against the ticking clock of the ship’s departure. You can’t really ask for a second take of that.

Britain’s Biggest Warship is the second project I have worked on with Chris Terrill. The other was Marine A: The Inside Story, a Panorama film on former Royal Marine Alexander Blackman, who was jailed for shooting and killing a wounded Taliban soldier.

That involved potential issues of contempt of court and the Official Secrets Act, so I have learned not to expect a smooth trip with Chris. We have certainly had some rewardingly robust but always friendly debates in the office and the edit suite.

INTIMACY AND CANDOUR

What marks Chris out is his extraordinary work ethic and absolute commitment to his craft. He simply loves what he does and that shines through in his films – his one-man-band approach creates a unique sense of intimacy and candour.

We’ve made yet another series of which I’m really proud, and I look forward to my next trip with Chris.

No comments yet