National Geographic’s Drain The Oceans makes archaeology accessible and fun by taking a ‘cinematic and tabloid’ approach to reveal what lies beneath the waves, says Phil Craig

Production company Mallinson Sadler Productions

Commissioner National Geographic

Length 15 x 60 minutes (series two); 10 x 60 minutes (series three)

Executive producers Crispin Sadler; Phil Craig; Tom Adams; Jobim Sampson

Series producer Savas Georgalis

Head of production Kathy Hale

Post house Clear Cut Pictures

“Phil, it’s US cable. It’s not ‘woo, woo, woo’, it’s ‘bang, bang, bang!’”

Pretty much everything I have ever learned about documentary production can be traced back to notes from my all-time favourite US network exec, who remains unnamed here, and this was definitely one of the best.

That was more than 10 years ago – I think that today we’re living in an age of both ‘woo’ and ‘bang’, as proved by the success of the series I jointly run for National Geographic: Drain The Oceans.

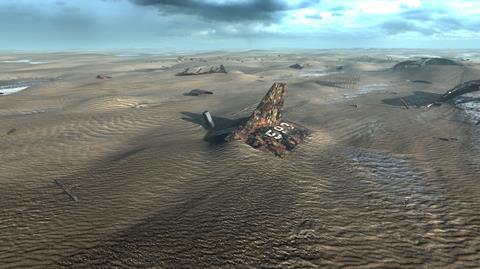

The concept is brilliantly simple and an instantly appealing way of making archaeology accessible and fun: what if we could remove – or drain – the water? What would we see and what could we learn?

My friend Crispin Sadler spent six years making six single episodes of Drain, laboriously stitching together complex international co-pro deals, hustling around the markets to plug funding gaps. And they worked – especially for Nat Geo.

Eventually, the network asked him to make more. That’s when I got involved, at first along with Australian indie Electric Pictures and then as a partner in Crispin’s company, Mallinson Sadler Productions (MSP).

Hamish Mykura, executive vice-president of programming and development at Nat Geo, calls our approach “cinematic and tabloid”.

We still have the ‘bang’ – the bold story beats and the ‘roll up, roll up’ appeal of subjects like Nazi warships, secrets of the pharaohs and lost ocean liners.

But there’s plenty of ‘woo’ too – a sense of grandeur and mystery, stylistic flourishes and delicate musical scoring that’s a long way from what we used to call ‘the Discovery drums’ back when everything in cable-produced non-fiction was ‘bang, bang, relentless bang’.

After all, Drain is sitting on the same network as Nutopia’s high-end One Strange Rock and we want it to have some of that flair and finesse. The show is not a simple format.

Hamish, alongside original commissioning editor Carolyn Payne and our Nat Geo boss in Hammersmith, Simon Raikes, really presses to make our storytelling different.

So the drain device – crafted by the CGI team at 422 South in Bristol – is rarely just an illustration and certainly never wallpaper.

It sits at the centre of our thinking and is our critical story-driving machine, celebrated in heightened language and emotional music every time we deploy it.

In a recent episode on the China seas, we told the story of powerful rivalries and lucrative trading routes that left these waters strewn with shipwrecks, from a 12th-century Mongol invasion fleet off the coast of Japan to long-lost ships laden with porcelain along the coast of Vietnam.

These now provide archaeologists with amazing opportunities to study time capsules from the past and piece together a key story of human civilisation, trade and politics.

On the face of it, this sounds a little academic and maybe even a little ‘woo, woo, woo’ but, in fact, it’s a hugely enjoyable watch because you get to see astonishing evidence emerge from under the water and the silt, which is then reassembled into a ‘ghost ship’ as if by magic.

And we’ve found that our drains open up stories that might challenge other formats. One of the unspoken rules is that US audiences won’t watch programmes about World War I, but by calling an episode based around the Battle of Jutland Drain The Ultimate Battleships, we found a way that works just fine there.

The key is the focus on finding these metal monsters at the bottom of the North Sea; more akin to a cool video game than a black-and-white archive history show.

Making discoveries

To access great stories, we work closely with the archeological community. Partly thanks to our rising profile on the network, and partly due to our tireless lead series consultant James Delgado, researchers are now bringing their new discoveries to us.

We very much want to retain their confidence in our journalism, so we never claim that the drain itself ‘discovers’ anything or that it’s a magic archaeology machine. We always show or refer to the data we are using, and seeing it being gathered is an exciting part of the format.

That said, whenever we can, we like to hold back the precise nature of what’s been discovered until we ‘see it’ for the first time in the CGI. It’s a lot more fun that way and sometimes means we tell stories in a surprising, non-chronological order.

We don’t claim to find anything that hasn’t already been found. However, in our MH370 special – and in a show on the Bermuda Triangle – we do create ‘educated guess’ drains.

In other words, if we could find the missing plane, it would probably look a certain way, based on all previous discoveries of commercial airliners on the seabed.

In our latest episodes, we’re pushing further into ‘historical drains’ too – seeing things as they once were. This helps us apply the drain concept to several subjects we might never have considered before: engineering, social history or even current affairs.

That’s why we have upcoming episodes on the Gold Rush, the Cold War, New York City and a story (currently under wraps) that’s been making international headlines for the past 12 months.

With a couple of dozen episodes on the go right now, it’s an exciting if head-spinning time. Building a machine like this without losing the soul of the series has only been possible because of Crispin’s continued focus, along with an incredible editorial team led by exec producer Tom Adams and our head of production Kathy Hale.

Under the creative command of Dave Corfield, 442 South has been busy refining the drain idea, and is now creating what Raikes calls ‘camera-real’ CGI images of real beauty.

We no longer simply ‘drain’ the water away and fly over an undersea object; we now imagine what we’d do if we had a classy DoP on the sea bed, picking shots, throwing focus and attaching GoPros to parts of the wreck so that water pours past the lens as it drains away.

For us, going large also meant going to London – to an extent. Crispin, local production supremo Adaire Osbaldeston, Sarah Pitt’s drain development team and about a third of the episodes are still based in MSP’s original Bristol home, while I head the London office.

From here, we’re developing new ideas for new customers. Clear Cut in Brook Green was our original landlord as we tried to set up a complex production from a couple of windowless edit suites and run conference calls out of its car park and furniture store.

We’re now in slightly smarter digs around the corner but doing all our London offlines in those same edit suites.

Through the talent and energy of more than 100 members and access to some incredible science, we’re showing things that have been invisible for centuries, and we love doing it.

All our drains are special, providing moments of revelation, astonishment and even joy. We’re continually asking the audience: “How amazing is this?” As we look forward to yet more expansion of our output, we’re asking ourselves the exact same thing. Woo!

No comments yet