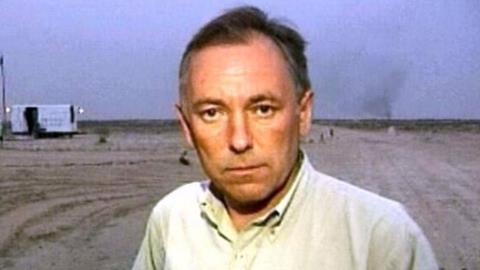

Comment: Ex-ITV News managing editor Robin Elias recalls the terrible day in Basra, and a moving return trip to Iraq

It’s not easy to identify ITN’s finest hour over 65 rich years of broadcasting history. It is easy for me to remember its most traumatic.

It was 22 March 2003, and I was the duty manager sitting on the Foreign Desk in the ITV Newsroom when an early morning call came through from southern Iraq. It was Barbara Jones, a reporter with the Mail on Sunday.

In a shaky, but calm voice, she told me that an ITV News team had come under fire south of Basra. There had been casualties, she said: “I think Terry Lloyd may have been killed.”

In an instant, my years sitting in the safe and comfortable chair of the programme editor were catapulted forward into the real world of personal tragedy, excruciating pain, and devastating loss. After putting the phone down, I sat in stunned silence. In the brief and frantic preparations for covering the war, we’d put into place a detailed ‘to do’ list in the event of any of our teams being hurt.

We’d devised a strict ‘reference up’ protocol to report events rapidly to the right people in the right order; every manager had been assigned next-of-kin contacts so that they’d hear any bad news first, and direct from someone they knew; we’d been instructed to keep a contemporaneous note of all communication with the front line.

That careful planning stood us in good stead, but nothing could adequately prepare us for the agonising task of breaking the news. We’d had plenty of experience dealing with “the bereaved” – now we found them within our own ranks. It was simply horrible.

The following hours passed in a blur. Managers were dispatched to visit the families of Terry Lloyd, his camera operator Fred Nerac in Belgium and his translator Hussein Osman in Lebanon.

Strength and dignity

I marvelled at the strength, compassion, and dignity of everyone involved. Terry had led the team. I’d always regarded him as the classic ITN reporter. He had an easy confidence about him – always smiling, always willing to put his hand to any task, but his unfailing good humour belied a gritty determination to get the story. His news agency background taught him guile and a street-wise shrewdness.

On the international front, he’d broken the news that Saddam Hussein had used chemical weapons in Halabja. He was simply a great reporter.

His camera team of Fred and Daniel Demoustier made a formidable alliance. How I envied their closeness – the bond that is unique to news teams in the field.

This was the territory of radicals, and a world away from that cosy chair in Gray’s Inn Road.

I was later assigned to the family of Hussein Osman. That took me on a journey like no other in my comfortable career. It involved meeting Samira, Hussein’s stoical and humble wife, and his two lovely children, Abdellah and Fatme, in Beirut. The children were full of fun and mischief, apparently resilient to what had befallen their family.

Terry’s body had been identified pretty swiftly. Fred and Hussein were officially “missing”. This introduced me to the world of military investigations and forensic examination.

ITN lobbied vigorously with the Ministry of Defence, the American military, and with foreign governments and NGOs, but it was a long and painful year later that military investigators finally recovered a body fragment. After an anxious wait, we were told that it matched Hussein’s DNA: a final and devastating blow for his loyal family.

I travelled back to Lebanon for the funeral, and this time left the comparative safety of Beirut for a nervous journey through the lush vineyards of the Bekaa Valley to the dusty town of Baalbek. This was the territory of radicals, and a world away from that cosy chair in Gray’s Inn Road.

My fears of a cold and hostile reception were quickly dispelled. A chair was reserved for me in the front row, alongside Hussein’s closest family.

I sat next to his father Husni, a gracious and dignified man. Relatives queued to shake my hand. There was a parade through the town, and at the cemetery gates, Samira and the children said their final, tearful goodbyes.

At the graveside, hundreds of men and boys chanted their respects. I was shielded from the throng of mourners and then carefully escorted back to my car and driver.

There was a great pride that Hussein had worked for a renowned British news organisation. Everyone thanked me for the support we gave the Osman family. As his coffin was lowered into the ground amid chaotic scenes, I was reminded of others who’d died. Each year at the RTS Television Journalism Awards in London, journos in evening dress stand to recognise a terrifyingly long list of those killed doing their job. We owe them everything.

In our business, it’s not so hard to recognise great journalism, brave reporting, and brilliant production. We’ve always been pretty good at hero-grams.

But the proudest memory I will take from my 38 years at ITN will be our response to the events of 2003. It was when the strength and camaraderie of the ITN family was truly tested. And – in great sorrow – I believe we passed the test.

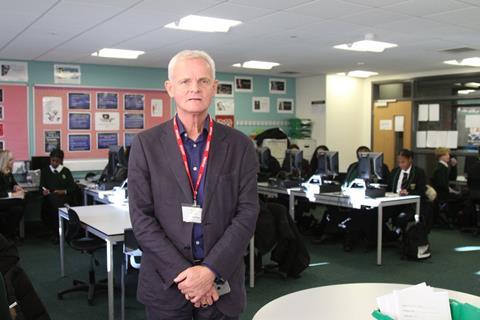

Robin Elias worked at ITN for 38 years, before retiring in 2019

No comments yet