Should the rise of AI be a concern for the industry? Broadcast’s survey of indies, broadcasters and post houses reveals the impact the technology is having

Is AI a vital tool that can make the industry more efficient by speeding up the production process, or are we training up a sentient technology that will ultimately replace us? Even outside the creative industries, AI-generated images, articles and videos produced at a few clicks of a button – whether to cut costs, showcase creativity or simply for fun – have become part of daily life.

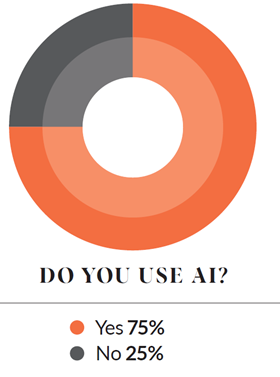

So how widespread is AI’s use, where is it adding most value, and what are the major concerns? Broadcast reached out to indies, broadcasters and post houses to produce a snapshot of industry attitudes towards, and use of, AI. Of the 52 businesses that responded, 38 (73%) are already using it in some form – 15 of them daily.

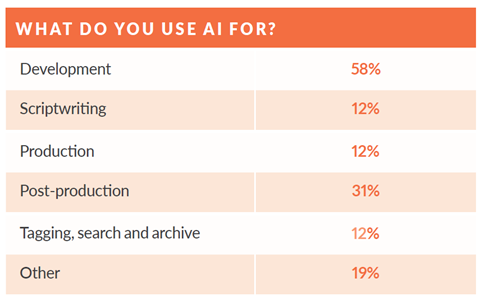

Right now, AI is seen as a driver of efficiency, and primarily as an aid to development, identified by 24 of those surveyed in both cases. It is doing the ‘drudge’ work, freeing up time to focus on more creative work. Specialist tools such as Firefly and Claude, meanwhile, are aiding post-production, whether creating placeholder graphics or, as one respondent put it, “cleaning up crappy video footage and poor audio”.

Everyone who reported working with AI is using ChatGPT, the tool that has arguably become synonymous with AI in wider society. Due to its non-specialist nature, all types of companies are deploying ChatGPT to write and organise notes, manage tasks and speed up writing transcriptions, treatments, storyboards, synopses and billings.

Several say they are using it for pitch decks and sizzle tapes, whether to help shape text – one says they draw on AI-generated copy as “an elaborate thesaurus” – or to create audio-visual references such as placeholder voiceovers, video or images. Midjourney and OpenAI’s Dall-E are the most-used tools in this area, while one of the next-generation models, OpenAI’s text-to-video application Sora, promises to create any image at broadcast quality.

AI can be powerful in honing ‘stream of consciousness’ notes and one-line pitches into fleshed-out proposals – as one indie respondent notes. Where broadcasters don’t fund development, AI is a low-cost aid to generating and presenting ideas.

That said, there are vexations over its current use, centred largely on quality, which most respondents expect to improve in the near future. But, one notes, for now, “AI writing tends to be bland and generic, and it’s as much effort to use it as not”.

More succinctly, one laments AI’s habit of “scraping IP and spitting out generic rubbish”. Another posits the reputational risk of public service content in particular being open to misuse – the BBC, for one, is known to be significantly limiting AI use for fear of scraping its vast archive. Then there is the fear of the jobs that could be lost, and the potential de-skilling of junior staff as their traditional roles are outsourced.

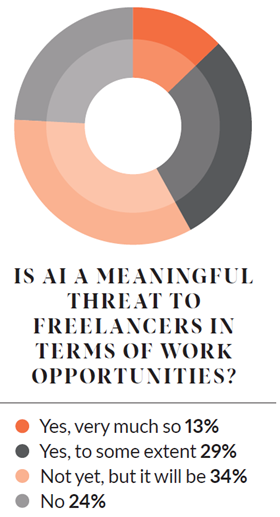

Risk to jobs

Explaining that they deploy AI for early-stage research, one indie exec says: “Sadly, we now don’t need to hire development researchers or APs, and more work can be done by a much smaller team.” They expect specialisms such as production music to follow suit, predicting that this could become indistinguishable from human-created work within a year.

This is backed up by another respondent whose first job in the industry – logging rushes – is now done at their company using the AI-powered Trint. One respondent likens AI to having “a very quick, not very bright assistant” – they would not rely on it for anything significant, but nevertheless expect it to replace junior researchers in time. Another estimates that AI can produce in 30 minutes what would take a researcher two hours.

While AI needs a human hand to guide it, some observe that the risk of job losses in technical areas, from design to sound and editing, is far greater.

“People working in graphic design may fi nd their skills not being required so much,” one respondent notes. “Currently, we are training our development staff on the use of AI, so it is just adding strings to their bow. But specific skills around graphic design and some editing work may be in jeopardy.”

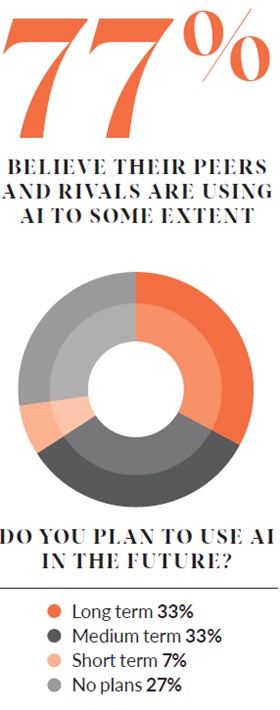

Almost all of the respondents not currently using AI expect that to change in the future, whether they welcome it or not. Almost half of these say they have ethical reservations about the technology, while a third admit a lack of knowledge or understanding is holding them back.

The biggest concern of our respondents is IP infringement, from ideas to scripts and replication of talent’s voices and images. As one puts it: “The modelling has been created using copyrighted material without consent.”

AI is certainly sparking debate about what constitutes creativity and originality. If, as one respondent says, “everything we watch, read and learn as humans is synthesised from other people’s work”, with “only the occasional genius creating something original”, then it follows that we should be able to extend existing copyright checks to AI-generated content.

Resistance is futile

Nevertheless, the increasing difficulty of spotting the difference between human-created and ‘deepfake’ AI-generated creations, caught in an infinite loop of data that is “used, stored and regurgitated”, is a major worry.

The free-for-all nature of accessible AI even led one unscripted indie exec to gloomily proclaim it will be “the end of TV as we know it” in 20 years.

They predict we are at most “a decade away from people being able to personalise their own content. ‘AI-player: show me a detective movie set in the 1930s with The Rock playing a hardnosed detective…’.”

But above all, respondents acknowledge that it is early days and expect their use of AI to ramp up in the coming months. As with the dawn of any new technology, there is a sense that resistance is ultimately futile, and AI is already part of a creative organisation’s toolkit. But away from the initial hype, it is in the industry’s collective power to understand where AI sits in the value chain, and learn how to harness it for good.

One respondent offers this reality check: “There is a lot of hype – it’s not as good as the marketing says it is (yet) - but it has huge potential. However, the performance needs to substantially increase before it can be gamechanging.”

At this juncture, our snapshot shows an industry split between evangelists for AI’s potential to revolutionise production (and storytelling, through the creation of lifelike simulations of actors and presenters) and those who want it to remain a powerful support tool for creatives who know how to use it to their best advantage.

Both camps say that regulation is needed to tame this technology, though they are equally split on whether this should be the duty of Ofcom or broadcasters and streamers – a handful also lay the responsibility at Pact’s door.

Either way, 74% of respondents say broadcasters and streamers have not issued any “meaningful” guidance on using AI, compared with 29% who say they have.

“We can’t rely on AI - it’s not creative,” one respondent concludes. “It can offer a good foundation for us humans to then build on, but we mustn’t depend on it fully because it’s pretty soulless.”

Or to put it another way: “The adage is true: ‘AI won’t take your job – but someone who knows how to use it will.’”

Survey production and editorial support by Aliza Dams, Matilda Mitchell Graham and Georgia Bailey

1 Readers' comment