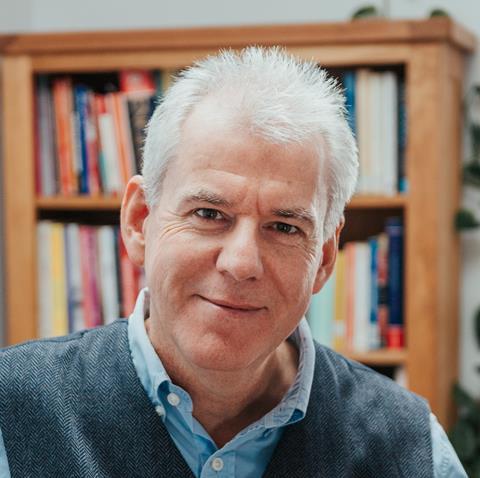

Bournemouth University’s Dr Richard Wallis says Covid-19 catapulted the industry’s bad habits into the spotlight

Out with the old and in with the new - January is a time for fresh starts and resolutions.

Last year was bleak for many who work in TV. Just how bleak becomes all too apparent from the preliminary findings of the State of Play survey conducted in December and published on Monday this week and Covid-19 is not a sufficient explanation for this startling vote of no confidence in the TV industry by its own workforce.

As the report suggests, the pandemic has been the x-ray that reveals long-term underlying skeletal fractures. The good news is that we’re finally talking about them.

Research suggesting that the UK’s TV industry has a systemic problem in the way it employees is hardly new. Decades have elapsed since the BFI’s Television Industry Tracking Study (carried out between 1994 and 1998) gave us early warning signs. It’s been almost 15 years since Reena Bhavnan’s comprehensive report into barriers to diversity within the film and television sector was commissioned by the UK Film Council.

It’s taken the recent pandemic crisis for enough people to start to ask why the industry works the way it does

The last ten years has seen a steady flow of research variously warning of the industry’s problem with unfair recruitment practices, lack of diversity, poor management, lack of professional development opportunities, entry-level exploitation (including a persistence in the practice of unpaid work), mental health issues, susceptibility to a culture of bullying, high levels of attrition by mid-career… The list has become a depressingly long one.

Given the consistency of earlier research with the State of Play findings, the $64m question must be why nothing has changed before now. The inevitable answer is that ‘it’s complicated’. TV work is highly sought-after and tough to get into. There’s widespread acceptance of the idea of ‘paying one’s dues’ - an expectation that you have to earn your privileges.

It’s also highly competitive, both to get in and to get on. The cumulative effect of all this is to accept that it’s all ‘just the way the industry works’. It’s taken the recent pandemic crisis for enough people to start to ask why it’s the way the industry works.

The acceleration of the structural and operational changes over the past 20 years has shifted the industry towards wholesale reliance on a freelance workforce. It’s a leaner and meaner way of operating.

The industry is now hailed by government and policy-makers as one of the UK’s great ‘success stories’. In many ways it is. But if the industry has been generating an annual trade surplus of almost £1bn, it looks as if it has done so at the expense of its workforce.

The Edinburgh TV Festival themed its August roundtables as a ‘Time for Action’ - this is hardly an overstatement; more than a third of this workforce say they would have chosen differently had they known at the start of their career what they now know.

For the sake of this industry’s future, there cannot be a return to business as usual. It’s not about everybody trying to be nicer. It will require those who commission programmes, and those who are commissioned to make them, to step up and take what is undoubtedly their responsibility. But what a great new year’s resolution that would be.

Dr Richard Wallis teaches film and television at Bournemouth University and has worked as head of learning and executive producer for Twofour Group. The State of Play preliminary report was published by Bournemouth University, Bectu and Viva La PD on 11 January.

No comments yet