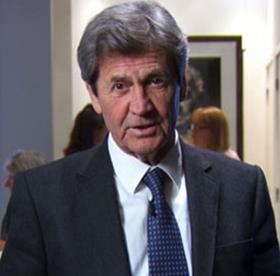

Huw Wheldon’s ‘fierce, interfering, yet helpful and inspirational’ style opened the broadcaster’s eyes to TV’s power to make arts for everyone

Monitor: Robert Graves

BBC2, 1959

We didn’t get a television at home until I was 16 and there was none at all at university. But during one vacation, whilst staying with a friend in London, by chance I saw a programme that changed my life.

It was an edition of BBC2’s Monitor arts series about the writer Robert Graves, in which he explained and showed on screen the many drafts of one or two of his poems.

I’d read Grave’s historical novels set in the Rome of Claudius, and his First World War memoir Goodbye To All That. It never occurred to me that he was alive, let alone willing to talk directly to a wide audience about his work as a writer. Most great artists in my repertoire were dead.

I was transfixed. Here was the man, vividly alive and willing to share his most intimate trade secrets and methods.

Television brought the arts from an alien planet right into the home and found a scattered audience. You just had to flick a switch like an electric light.

When I joined the BBC in 1961, the only television programme I was at all interested in was Monitor. Huw Wheldon, the editor and presenter, took me on board, for which I am forever grateful.

The people who worked there were exhilarating. Ken Russell had started on his glorious run of radical arts films. Humphrey Burton was bringing terrific zest to classical music programmes. David Jones, who was to go on to become a director at the RSC, took over drama.

It was like being given an Aladdin’s lamp. It had never occurred to me that work could be like this. Huw was fierce, interfering, but also helpful and inspirational.

Above all, he had no doubt that arts programmes mattered and that television ought to acknowledge and respect their place in society.

I saw it as a way to reach thousands even millions of people like myself whose access to the Arts had been greatly limited by education (lack of), finance, geography and psychology.

Television brought the arts from an alien planet right into the home and found a scattered audience. You just had to flick a switch like an electric light. And on television over the last 50 years, we’ve been able to see some of the greatest artists on the planet.

I’m convinced that had I not caught that programme one Sunday evening in my friend’s North London flat 60 years ago, I would never have come to appreciate the power of television to make the arts accessible and often of the highest level.

- Melvyn Bragg presents In Our Time on Thursdays at 9am on Radio 4

A Window on the World

How TV broadened viewers’ horizons, including Melvyn Bragg on Monitor and David Glover and John Smithson on Horizon

No comments yet