The shades of grey in Paul Hamann’s death row film, coupled with his swashbuckling and sincere presence, taught the Label1 creative director the power of documentaries

Fourteen Days in May

BBC1, 1987

Dad was at work. Dad was always at work.

That meant I got to sit in his armchair in the corner of the living room to watch telly – the one he’d drape his legs over and read the newspapers in.

It was 9pm, November 11th 1987. The remote control hadn’t been invented yet. I liked the fact that dad’s chair was closest to the telly and I didn’t have far to move to change the channel.

Alone in the living room, I was watching Paul Hamann’s Fourteen Days in May. Like all programme titles then, it was opaque. The title gave no clue to the blistering 90 minutes that lay ahead.

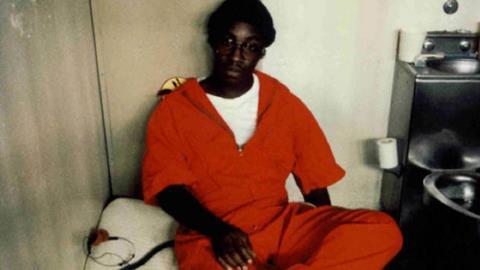

The film told the story of the last two weeks in the life of Edward Earl Johnson, a young African-American executed in Mississippi for murder and sexual assault.

Hamann, and Johnson’s British lawyer, pioneering civil rights activist Clive Stafford Smith, were convinced of Johnson’s innocence. And – after watching the documentary – so was I.

In those days, the BBC had an official line on stuff. Things were reassuringly binary. Hamann’s film was anything but.

Here was a conundrum. Back in those days, the BBC had an official line on stuff. The news was read by stone-faced Kenneth Kendall. The good guys wore white hats and the bad guys, black ones. Things were reassuringly binary. Hamann’s film was anything but.

It showed every dimension of the emotional, legal, political and racial mess that those 14 days stirred up. From the pre-execution testing of the gas chamber, carried out by a crew of jovial rednecks, to the sly wisdom of Johnson’s fellow death row inmates.

From the manifest turmoil in the heart of the prison’s own governor, to the tenderness of Johnson’s last meal. Shrimps with cocktail sauce: he had never eaten them before.

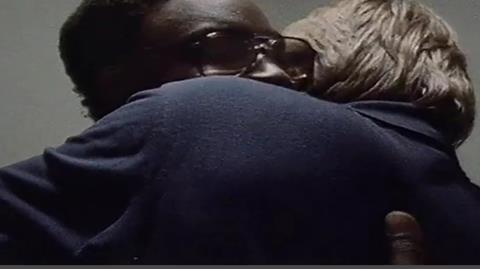

And then, something I had never seen in a piece of factual television. Hamann, the producer-director, stepping out from behind the camera to enter the shot and embrace Johnson and say goodbye, minutes before his execution.

Hamann’s masterful weave of scenes, dragged towards the glowering darkness each day by the irresistibility of the timeline, combined with his own swashbuckling and sincere presence in the mix, challenged me to make up my own mind about what was going on.

And I did. I decided that the death penalty was immoral; and that I wanted to make documentaries for a living. When, later that same evening, my dad finally came through the front door and reclaimed his favourite seat, that’s exactly what I told him.

Hamann’s fascination with the penal system endures, and he still produces high-quality films within British prisons. There’s a market for them: our industry’s fascination with true crime has never been stronger.

Sadly, for every piece of Hamann’s work in this genre, that of his heir apparent Paddy Wivell, and BBC3’s excellent Life and Death Row, there’s a slew of dispiriting, meaningless pulp.

Those of us who believe that the world is still a place where the good guys wear white hats, and the bad guys, black, are strongly advised to seek out a copy of Fourteen Days In May.

- Simon Dickson (pictured in 1987) is the co-founder and creative director of Label1 Television and an RTS Society award-winner for BBC2’s fast-turnaround documentary series Hospital

Topics

Crime & Punishment

Detective dramas and prison docs from Kieran Doherty on Columbo and Lisa McGee on Murder, She Wrote to Ed Coulthard on The Thin Blue Line

- 1

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Simon Dickson: Fourteen Days in May

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

1 Readers' comment